The first contact between the people who inhabited the remote areas of Eurasia took place in prehistory. In later periods, various products found their way from East to West and vice versa. In addition to artifacts, materials, resources, animals and plants, the exchange of ideas, knowledge and experiences, human migration, but also the transmission of various pathogens were significant. The most famous route or the network of roads connected east and west of Eurasia was called the Silk Road.

The name Silk Road (Seidenstraße) was coined by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in the second half of the 19th century. Although von Richthofen also used the plural version of the name, usually, the public image presented that there was a single intercontinental communication. However, such a formulation is not correct because in reality there was not one complete communication line or road; instead, there were a series of smaller and larger routes connecting the areas from the Korean Peninsula and China to the Mediterranean. In parallel, several routes went through Central Asia, parts of Russia, the Middle East and present-day Turkey.

“The name Silk Road (Seidenstraße) was coined by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in the second half of the 19th century.

In addition to land routes, maritime routes were also active, including a wider area from the Far East to East and Northeast Africa. About that connection between east and west or Silk Route, it was complex communication and an infrastructural network consisting of roads and sea routes, lodgings, shrines, trade caravans, marketplaces and cities should therefore always be spoken by using the plural name — Silk Routes.

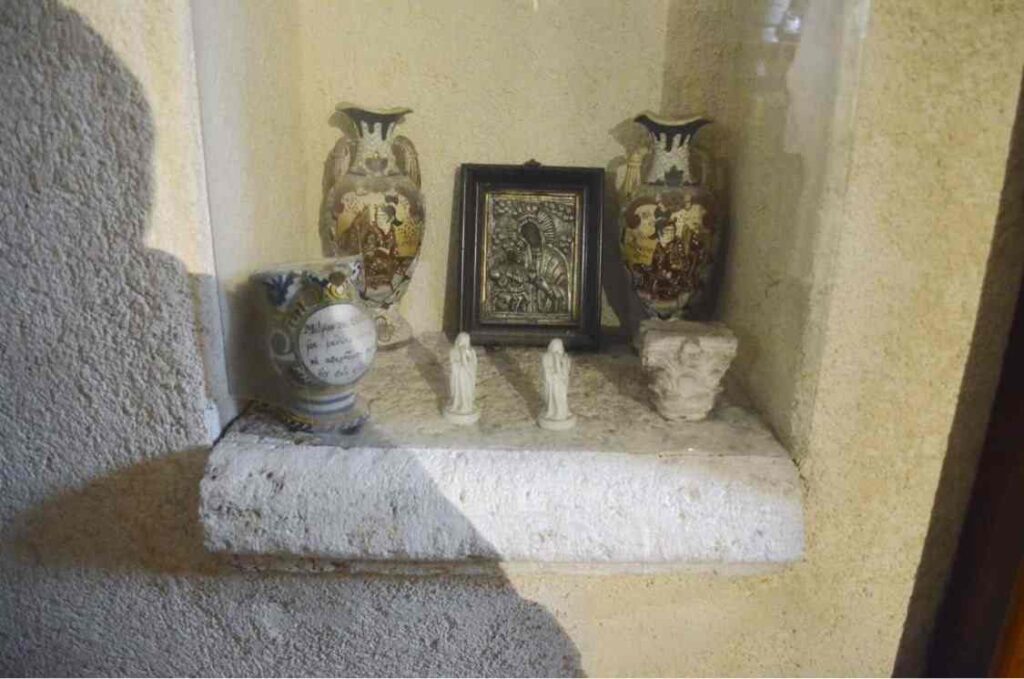

Chinese objects on the islet of Our Lady of the Rocks in Montenegro

(private photo)

Besides, the name of the road network hides another difficulty. Namely, although we know today that silk was not the only or even the most important product traded, it became part of the name, which further distorted public opinion about trade and communication within the Eurasian continent. Silk was an exotic and luxurious product, so it was not in mass usage and was not widely traded. However, researchers of the 19th c. like von Richthofen viewed silk as the most luxurious and impressive product to arrive from the Far East to Central and Western Asia and Europe, so it’s not surprise that they named the entire route after it. Also, the trade of food, beverages and spices, plants and animals, metal, ceramic and glass products, and raw materials and works of art was of much greater value. In addition to all that, there was human trafficking and the slave market.

Speaking of initiating and maintaining all kinds of encounters and touches of East and West, we should have in mind that human resources were crucial. Human efforts in achieving the security of goods and people on a long journey, and the organization of sufficient resources for people and animals, overcoming the geographical features of the area, as well as all political instabilities, were crucial for the systematization and maintenance of trade networks. The ways of silk depended on human efforts, so they changed accordingly.

Although the relations of East and West date back to the past, the so-called The Silk Routes, according to traditional historiography, was determined only by the establishment of more stable and larger political entities, i.e. empire. The Roman and Han Empires were primarily leaders because they were situated on the western and eastern points of systematic communication. However, despite the fact that some archaeological finds such as Roman glass in tombs in the cities of Guangzhou and Luoyang dated to the 1st century BC and AD, as well as Chinese silks in the West, confirm the presence of certain contacts in the time of Rome and the Han dynasty, it is challenging to determine the existence of systematic communication, or to follow the line/trip of an object that would show direct contact. There is no doubt that some Roman and Chinese merchants and explorers traveled far from their homes, but it is still difficult to prove that they regularly reached China and Rome by participating in the maintenance of a well-organized communication network. It is very likely that the exchange of goods, knowledge, ideas and people took place in many directions, in which various political entities, peoples and indigenous communities such as Parthians, Sassanids, Seleucids, Pontus, Armenians, Bactrians, Sogdians, Jews, Arabs, Indian and many others such as nomadic communities played a major role. These communities had different roles in permeating the west and the east, from production (producers, suppliers), trade (intermediaries, traders), protection (soldiers, priests) to crime (robbers, kidnappers).

In order to gain greater control over trade and economic exchange in Asian areas outside their home territory, the medieval empires Byzantium and the Sui and Tang dynasties organized political and military campaigns. Their common interest in Central Asia encouraged a much greater exchange of goods, people and knowledge. Chinese fine art in the Middle East, Byzantine figures in paintings and reliefs in China and the making of foreign sculptures, the appearance of exotic products such as the still undefined “golden peaches” in Chang’an, or in the remains of Byzantine money found in China show these links. But all these clues are still not enough to prove the existence of strong and structured trade links. Even the significant amounts of Byzantine money found in China are not strong enough evidence because much of that money was imitations used in China for funeral rituals and as, as Walter Scheidel writes, exotic jewelry made of gold and silver.

Monument to Marco Polo at Beijing Foreign Studies University

(privat foto)

The Silk Routes reached their peak after the Mongols conquered vast expanses of Asia and Europe. For the first time, they politically united the entire area where the traditional “Silk Routes” developed, creating the potential for strengthening trade, economic and political ties. After the military conquests, these areas enjoyed certain security for a relatively short time, which further facilitated the transfer of goods, people and knowledge. Therefore, it is not surprising that at that time the three most prominent passengers, Marco Polo, Ibn Batuta and Willem van Rubruk, undertook their travels, leaving written traces of China, and have been organized different exchange including Black Death, terrible disease which have been spread via Mongolian Empire and Silk Routes.

The Silk Routes continued to connect East and West even after the decline of the Mongol Empire, playing a significant role in the transmission of knowledge of goods and people and during the reigns of the Ming and Qing dynasties. However, these paths gradually began to fall into the background over that long period, especially during the reign of the Qing dynasty. Namely, the appearance of British, French, Dutch and Portuguese ships and, for example, the establishment of direct diplomatic ties with imperial Russia changed the nature and speed of various interactions between East and West.

In addition to the exchange of trade goods and services, the Silk Routes have significantly facilitated the exchange of ideas, innovations and knowledge. In addition to the above, this network of communication has contributed to the spread of religions, such as Christianity and Islam to the East and Buddhism to the West, as well as permeation in culture and art. The key importance of the Silk Routes as a symbolic connection between East and West, but also a territory of huge Eurasian space full of archaeological remains, is evidenced by the UNESCO initiative from 2014. The Silk Routes entered the World Heritage List and became a common protective heritage that will increase scholarship, research and tourism.

Bibliography

Hill, J. E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE. Scotts Valley, California: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

McLaughlin, R. (2010). Rome and the Distant East: Trade Routes to the Ancient Lands of Arabia, India, and China. London & New York: Continuum.

Ning Qiang (2004). Art, Religion and Politics in Medieval China: The Dunhuang Cave of the Zhai Family. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Powers, M. J. (1991). Art and Political Expression in Early China. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Whitfield, S. (1999). Life Along the Silk Road. Oakland: University of California Press.

Hopkirk, P. (1984). Foreign devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press.

Liu Xinru (1998). The Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Interactions in Eurasia. Washington DC: American Historical Association.

Saje, M. (2016). Zgodovina kitajske (History of China). Ljubljana: Društvo Slovenska Matica.

Yung, P. (1987). Xinjiang: The Silk Road: Islam’s Overland Route to China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

林梅村 [Lin Meicun]《丝绸之路考古十五讲》[The fifteen discussions about Silk Road archaeology] 北京大学出版社2006年.

The chapter titled The Silk Routes has been part of book: Z. Stopić, G. Đurđević, 2021, Svila, zmajevi and papir: kineska kultura, civilizacija, povijest i arheologija (Silk, Dragons and Paper: Chinese Culture, Civilizations, History and Archaeology), Zagreb: Alfa (in Croatian).

Topfoto: Omer Farooq, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Om “Stemmer fra verden”

Serien ’Stemmer fra verden’ er en samling af internationalt materiale, som kan bruges i undervisningen til konkretisering af den store historie. Disse menneskers stemmer og beretninger kan knyttes til forskellige emner i historieundervisningen. På en måde er de anvendelse af historien på mennesker i dag.

Tanken er at fortsætte serien, hvis der er interesse for det. Har du ideer til serien, må du gerne skrive til mirela@redzic.com

Forfatter(e)

Goran Đurđević (Djurdjevich) is a Croatian archaeologist and (environmental) historian who is Ph.D. candidate of Archaeology at Capital Normal University (CNU) in Beijing.

Zvonimir Stopić

Dr Zvonimir Stopić is an Assistant Professor at Capital Normal University in Beijing, an Assistant Director at the CNU’s Center for Study of Civilizations (文明区划研究中心), and is a lecturer at the Zagreb School of Economics and Management (ZSEM).